What Debt Demands

An Excerpt from Kristin Collier's New Memoir

Happy New Year!

From the start, Debt Collective has brought working class people together to expose the injustice of being in the red due to our profit-driven healthcare, housing and education systems. We’re proud to carry that legacy forward by uplifting our member, Kristin Collier, whose new memoir, What Debt Demands, is a compelling testament to the power of debtor-storytelling. Please enjoy the below excerpt from Kristin’s book. Her words remind us why solidarity—specifically sharing our interwoven debt experiences—can help translate and ultimately shape our reality.

Alana, a freshman I met in the fall of 2023, was set to become one of the million students who rely on Parent PLUS loans each year. When we first spoke, she had just moved to New York City to attend an expensive liberal arts school. She explained to me that her mother raised her and her sisters alone, moving across the west and north-west before settling in Nebraska, where Alana went to high school.

“I don’t have a lot of memories of my mother growing up,” Alana told me, “because my mother was always working.” Her voice was bright and rising. In the past, she told me, her mother had worked at a warehouse and a kidney dialysis center, and now, her mother was employed at a Walmart distribution center, managing incoming and outgoing trucks, and at a doctor’s office, scheduling appointments. Alana, too, had worked multiple jobs, beginning with a local movie theater when she was in tenth grade. Later, she was hired at Starbucks, a role she was able to transfer to Manhattan, working almost forty hours a week on top of a full class schedule.

Alana chose her college from an internet search: What is the best college for becoming a book editor? Her school was at the top of the list assembled by her search engine algorithm, which she had faith in. Alana applied, was accepted, and decided to attend, even as she remained uncertain about how exactly she would pay for it. At her high school, they’d talked very little about college financing and, other than a cousin, she didn’t have any close family who’d gone to college.

When Alana was given her financial aid letter, she googled what all the terms meant, e-mailed briefly with someone from financial aid, and then enrolled, despite some of the details remaining unclear. “I’ll just take out loans,” she said to me, illustrating how she’d thought about debt at the time. “That’s very American.”

When I asked her how much she had borrowed, she said, “I’m not sure exactly,” which caused my stomach to jump. It was October, and school had already started. She explained that there was a gap in what the school offered her in merit- and need-based aid and federal loans, and her mother was awaiting approval for a Parent PLUS loan for around twenty thousand dollars.

I tried to imagine this number as a “gap” instead of what it was: a canyon. That the school would think that her mother should borrow twenty thousand dollars for just the first year of school pointed to a carelessness with students’ lives, as did Alana’s matriculation before the financing was finalized. It forced her and her family to fill this “gap” and to internalize it as theirs, which might have been less true had they been in their Nebraska living room, navigating this financing from a distance, before Alana had moved across the country, unpacked her room, enrolled in class, and opened her first course book. There was inertia. She was on the hook for this semester no matter what.

Alana offered to send me a photo of the aid letter. “Apparently my school has the most expensive dorms in the country,” she said. Next year, she hoped to save money when she lived off campus. The aid office at her school had not been much help; to each question she asked, she was directed to talk with her “parents,” despite Alana sharing that her parent, her mother, was not managing this process for her. “If we don’t get this loan, I’ll be back to square one. And then I don’t know what I’ll do,” Alana said, her voice sinking.

I felt tempted to tell her “It’s going to be okay,” but I couldn’t identify what I meant by “it.” I wasn’t sure that she and her mother would find the necessary gap money or that their indebtedness would qualify as a positive outcome. Their debt would be shared, and though the origins would be different from the one shared between my mother and me, there was resonance there that I couldn’t ignore. “Okay” in this circumstance would mean something else entirely.

She had not been sleeping much, she told me. “I don’t think there has been a class this week that I haven’t dozed off in.” Between working at Starbucks, sometimes seven days a week, her classes, and homework, she had no time for anything else. She did not list the uncertain funding as one of her stressors, though it must have been. Her current situation required a kind of cognitive dissonance: She should participate in her campus life as if it would go on for four more years even though the aid discrepancy might mean she couldn’t attend school next semester.

When we hung up, with the promise to talk again once she was further into the semester, I studied her award letter. Despite her school giving her $30,000 in scholarship money, the federal government giving her almost $4,000 in Pell grants, and the school offering another $4,000 in work study money, there was still an enormous cost of attendance that was left unaccounted for. She had already acquired the federal lending maximum of $5,500 and what remained was not $20,000 for the year, as she’d assumed, but $42,000.

That number startled me and I looked at it several times to make sure that I wasn’t misunderstanding. When I talked to my partner about it, I cried. “That’s an evil amount of money,” I said. I was especially moved that she wanted to work with books and authors someday. I didn’t see that as naive but hopeful, even as humanities departments collapsed across the country alongside the publishing industry, and editors’ wages remained stagnant. Alana believed in a world made more beautiful and interesting by the stories that reflect and expand it.

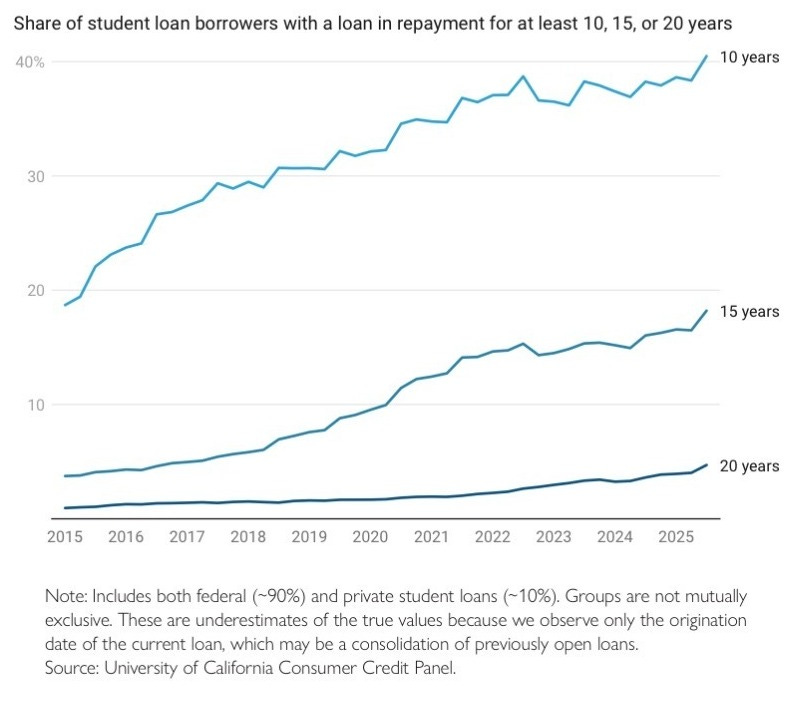

Her mother had already applied for the loan amount, and if she was approved, would likely need to borrow over $100,000 for four years of college. I wanted to tell Alana that her mother should not take out that loan and that she should not attend this school at all, but I’d known her for only an hour. I told her that she could ask me any questions she wanted, and that I would answer them honestly. I texted her a link to a group of first-generation college students that met on her campus. If I couldn’t keep her from joining the nearly 43 million Americans with student loan debt, and her mother from joining the 3.7 million families with Parent PLUS loans, then I could at least facilitate introduction to a group that might trade resources and advice, might make college less lonely.

Soon after our first call, Alana texted me that her mother had been denied the Parent PLUS loan because of a bankruptcy on her credit report. “Credit worthiness binds families’ possible futures to their collective pasts,” Caitlin Zaloom writes in Indebted. In thinking about debt’s ability to collapse and muddle time, I hadn’t considered that a denied application for credit, the very possibility of debt, works in the same way.

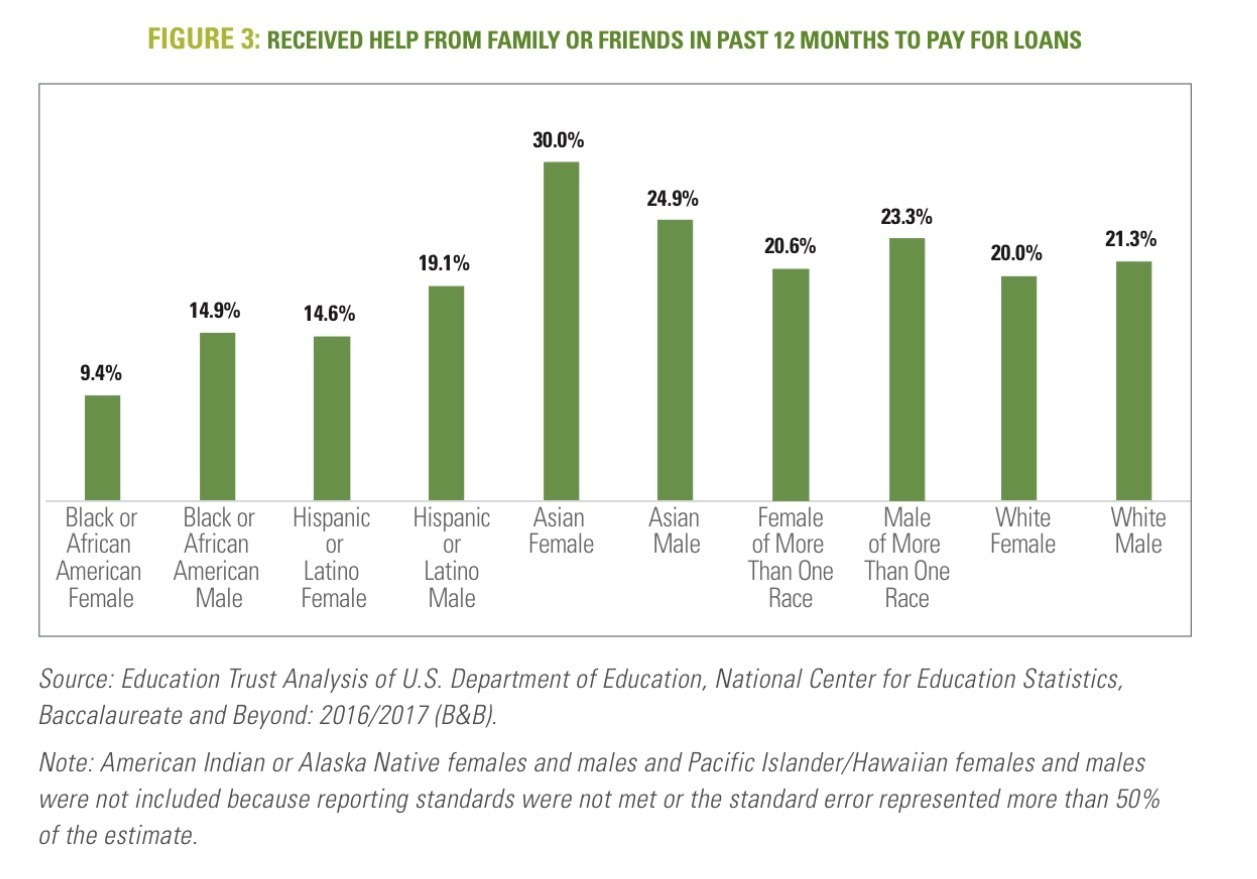

A 2011 Department of Education update to the Parent PLUS loan application restricted borrowing almost overnight by lengthening the time frame for parents’ credit history from ninety days to five years. This update impacted nearly 400,000 students, who suddenly didn’t have access to loans they assumed they’d receive under the previous borrowing terms. More than 128,000 of those students attended majority-Black colleges and universities, and many Black families faced a cost-of-attendance gap without a previously accessible resource to cross it. In response to a crisis for both schools and families, the government walked back the policy change. What remained was a clarity that these harmful financial products are also necessary for many Black students to attend school. As Zaloom considers the implications of the ability to “qualify” for these loans, she notes that to qualify is to “invest a subject with particular characteristics, and in the case of PLUS loans, the process of qualifying for a loan identifies families’ financial successes and failures as a result of their private actions.” While the government is insistent on seeing the student in the context of a certain version of family, they are unwilling to see the family in the context of national history.

After Alana’s mother was denied the loan, Alana, who is bi-racial, briefly considered asking a family friend to cosign on a loan before deciding not to. Lots of lower income students, and especially Black students, are implicitly and even explicitly asked to do this work: to summon resources from extended family and the community to make school possible. And many of their loved ones offer this support with joy and purpose. Although, on average, Black parents have less wealth than white parents, they are more likely to contribute financially to their children’s education. This is true at all income levels. I sensed that Alana didn’t want to ask her family friend because it felt like a new kind of debt to her—beyond owing the government she would also, in a sense, owe a friend. Instead, she was going to withdraw from her institution.

Over Thanksgiving break, I met her for coffee. We mostly talked about her classes—what she was reading and writing—and what life was like on campus. We talked about the future only a little. As Alana’s classmates packed suitcases to travel home, temporarily, for winter break, Alana would pack up everything. After a semester home, her hope was to return to school again, somewhere cheaper. For the next month, she’d concentrate on her limited time in New York City.

“It’s been a weird couple of months,” Alana said to me when we next talked in February. “I never expected my college experience to go the way that it did.” She was trying to accept that her first college experience wasn’t what she’d wanted it to be, a process that she thought would take some time. I was hopeful that she included the word “first” because it suggested that she believed there would be another college experience in the future. I’d sent along resources in December that included a list of “no-loan” schools, all of which are competitive, and an organization that works with first-gen students during the application process.

By her last days on campus, her roommates had all gone home already and she was moving through their shared world without them, an inversion of what would come next semester when they moved through the world without her. Just before the holidays, she learned that her creative writing professor had died by suicide, and she carried that loss with her as she looked at her room for the last time. “It wasn’t the greatest experience,” she said about her semester, but she still thought she was lucky to have it. “At least I had a chance to see what life would be like if it had gone another way.”

Though she was imagining a life in which the forces at work on her had converged in another way—if her mother had gotten the loan, perhaps—I think the other life she was imagining was more accurately one in which she had family wealth.

She remembered a day she skipped class to spend time with a friend whose own class had been canceled. That slot felt like an open door, a gift. At that point she already knew she was leaving campus. They wandered around a nearby neighborhood, walking into a book-store, where her friend found a beloved book from childhood, one her father had read to her growing up. As Alana shared this memory with me, I was aware that we’d never talked about her own father or what events precipitated her mother’s choice or her imperative to raise children as a single parent. “It’s one of my favorite books now,” Alana said. The memory was a layered one. There were fathers, absent and present, friendships—now physically distant. A narrative of intimate knowledge, and somewhere, in the background, a classroom continuing on without Alana. I wondered how it felt to reread that beloved book in Nebraska, away from the friend she bought it with.

Though watching her friends’ Instagram stories from far away felt “like a little stab in the heart each time,” because she so badly wanted to be back with them on campus, Alana was happy for them. She’d let go of the bitterness she felt at the end of the semester, and what she was left with, she earnestly told me, was gratefulness for the experience. She deserved to make meaning of her life without my intervention, but I had to resist telling her, “You were not lucky. You have enormous debt from a school you were, essentially, pushed out of—all because your family doesn’t have wealth and inherited knowledge about college financing.”

I struggled to balance Alana’s right to her own narrative, to the agency to say this was worth it, with my sense that the mechanism of debt creates and enforces this kind of thinking. We must “apply” for its kindness in the form of credit, and if we are denied, it is because we don’t deserve it. We must make payments toward this debt and are punished if we cannot. If we receive relief someday, through a government program designed to provide it or because our schools have defrauded us, we are “forgiven.” These concepts feel weightier when what we want to access with this debt is education, something Zaloom refers to as a “benefit of citizenship.” Right now, these benefits are given out unequally, she notes, with the largest share given to those who have historically benefited the most.

I asked Alana if she thought about her debt, to which she responded, “I think about it in that I’m putting money away from my job but also I don’t think about it.” It was out there, somewhere, she understood, waiting to collect payment from her, which it did the next summer when a collection agency contracted by her school contacted her to begin making $500 monthly payments on her $21,000 of unpaid tuition.

Unlike her federal loans, the unpaid tuition wouldn’t qualify for the income-based programs that would minimize interest payments and eventually, after long enough, relieve her of what was left. I didn’t say that. What I wanted to believe was—when it’s time for you to make payments, when you’ve graduated and are pursuing a career that brings you happiness and pays you a living wage, it will be different.

Alana didn’t know where she would go to school next or when, though she hoped it would be soon. She understood that the time she was away might dull her urge to attend. She wanted to use the momentum of her fall to swing her into a new school. Definitely one with good literature programs, one that offered comprehensive financial counseling, and, hopefully, no more debt.

Adapted from WHAT DEBT DEMANDS by Kristin Collier, published on November 18, 2025. Copyright © 2025 by Kristin Collier. Used by arrangement with Grand Central Publishing, a division of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.

Kristin Collier is the author What Debt Demands: Family, Betrayal, and Precarity in a Broken System (Grand Central Publishing), an organizer with the Debt Collective, and a visiting scholar and TREC community engagement fellow at Metro State University. She lives with her family in Minneapolis.

The year has just begun and already there is a lot to be mad about. ICE agents continue to spread violence throughout American cities while student loan borrowers face the financial violence of wage garnishment for past due balances the federal government has the power to discharge. We’ve got a lot of work ahead of us. We can’t do it alone.

Read Debt Collective’s’s latest article in Truth Out for student debt updates, consider becoming a member and or joining an upcoming call. Still, there are silver linings. We can use our rage as fuel to take precise action, organize, build power and demand an economy that works for us.

Powerful storytelling that exposes the structural cruelty baked into student lending. The detail about Parent PLUS loans being reconfigured overnight affecting 400K students crystalizes how policy shifts weaponize bureaucracy against the vulnerable. Alana's story hits hard because it shows debt operating as both barrier and sorting mechanism, pushing out students mid-semester after they've alerady relocated their entire lives. The wage garnishment piece at the end connects this to ongoing enforcement violence - the system extracts payment even from those it pushed out. I've watched freinds navigate this exact impossible math, balancing unpayable tuition against lost semester credits.